The East London Fashion Cluster

1. Executive Summary

Image Description: A black female model wears a yellow dress with applique detail in blue, orange, green and black and white. She wears very big linked hoop earrings in patterned fabric.

The vision for the East London Fashion Cluster is of a 21st century innovation quarter where fashion, technology, business and education meet; where companies compete to outinnovate each other; where they collaborate to turn heads, all over the world.

East London has a rich fashion and craft heritage, which has, in recent years shown signs of revival. The originality and vibrancy of its design culture is a recognised factor in London’s distinctiveness as a world fashion capital. And London as a fashion capital sits in the context of a world fashion industry worth an estimated US$3 trillion per annum.

This is a huge, export-driven sector of regional, national and global importance, but one that is sometimes perceived as an esoteric and ‘cottage’ industry. The direct value of the

UK fashion industry to the UK economy is estimated at £28.1 billion – twice that of the automotive or chemicals industries. Fashion’s total contribution to GDP is in excess of £50 billion – equivalent to 2.7% of UK GDP.

The scale of this opportunity means that there is no better sectoral or industry candidate in which to undertake a value chain analysis and propose innovations across that chain.

Fashion in East London can capitalise on its location in the heart of the UK’s knowledge economy to focus on its strengths in generation of IP. Bringing together fashion and

technology sectors will stimulate a ‘pull through’ of innovations in digital manufacturing that will have wider applications in other sectors. The current disruption of markets by digital technology and changing patterns of world trade means there will be no greater moment for the fashion industry to come together, demonstrate it understands its own structural issues and can bring forward innovative yet soundly based solutions for its own growth.

This report sets out how the fashion industry can skip a generation and lay the ground for London to be the undisputed world creative fashion capital by 2050.

London College of Fashion (LCF) is moving to East London as part of the development of a new Cultural Education District (CED) on the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Building on the legacy of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, the development consolidates LCF’s six existing sites into one new, purpose-built campus. It is a fantastic opportunity to secure its position as a global leader in fashion education, research, business incubation and social responsibility. It also places a duty on the College to contribute to the positive place-making, participation, economic, educational and social outcomes that CED is expected to deliver in an area of continuing social and economic deprivation, in spite of the success of the Olympics.

LCF’s move has triggered the opportunity to develop a wholly new environment for fashion innovation and a new destination for investment in fashion business in the UK. LCF will bring a global talent base to catalyse existing and emerging production corridors across East London and the Upper Lea Valley that are already witnessing the re-emergence of fashion manufacturing, reversing a trend of decades of decline.

The role of creative industries in driving economic growth, particularly in London, is well documented; less well understood is the scale, scope and potential of the UK fashion

sector. With annual output of £28 billion, it represents 22.2% of all retail GVA and 2.5% of UK manufacturing output. London is the centre of the UK industry, and a recognised

world fashion capital. It is the fulcrum of the UK’s participation in a global market worth an estimated US$3 trillion a year. The purpose of this piece of work was therefore to explore these issues, and specifically to understand the perceived revival of fashion in East London; to explore how LCF’s move might amplify some of these trends; and to see how the establishment of a dedicated organisation, the East London Fashion Cluster, could serve to accelerate growth and clear away the barriers to growth. The study was commissioned jointly by LCF and Greater London Authority (GLA), as both parties were interested in exploring how the rebirth of the fashion sector in East London could be accelerated by its proximity to other centres of knowledge capital.

But, in common with the rest of the city, East London faces a range of structural issues around access to workspace, finance and skills. The success of other sectors of the knowledge economy has exacerbated the conflict between the need to increase the supply of housing and to safeguard business premises. Existing fashion businesses in East London face a real risk of displacement, and with it their dislocation from a local workforce with the specialist skills needed to support high-end fashion manufacturing. Brexit, and the threat it represents to freedom of movement for students and skilled workers coming from other EU countries is a real concern to employers.

Fashion operates in global markets that are impacted by current geopolitical volatility. The potential imposition of tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade with Europe, and threats to free trade arrangements elsewhere in the world, could impose real constraints on what is an export-led sector.

Failure to address these barriers could lead to further tightening of labour supply and increasing costs of inputs that threaten the survival of specialist fashion manufacturing in

East London. This would in turn have a negative impact on the ability of new designers to translate their creative ideas into new collections; and undermine the ability of LCF and other fashion colleges to continue to recruit the overseas students who are both a source of income, new ideas and new businesses. The ratchet effect of loss of capacity, opportunity and reputation could ultimately threaten London’s status as a world fashion city.

Despite these risks, our research to date suggests that fashion design and retail are growing strongly in East London –more strongly than across the rest of the city – and that value added manufacturing is returning to growth after decades of decline. Fashion in East London and the Upper Lea Valley now contributes £1.4 billion to London’s economy and employs more than 36,000 people. It’s growing faster than the rest of London’s economy – output increased by 57 percent over the period 2010 to 2015, whilst an additional 10,900 jobs were created. And East London is driving the growth of fashion design, retail and manufacturing for the city, with an ever-increasing proportion of the capital’s fashion enterprises and employment now located in this quarter.

Recent initiatives could further accelerate some of these trends. Private sector investment in skills through projects such as the Fashion Technology Alliance and the Stitch Academy at Hackney Walk is being met by public sector support for the creation of new spaces for fashion retail and enterprise, including Hackney Walk itself, specialist manufacturing facilities at Building Bloqs in Enfield, and Fashioning Poplar, a project initiated by Poplar HARCA, LCF and The Trampery to convert disused garages into manufacturing space, studios, and training space for use by students, designers and ex-offenders to promote opportunities for local residents to develop craft and business skills and create new fashion enterprises. Plexal, an accelerator for fashion and Internet of Things start ups, established by the founders of successful fintech incubator Level 39, will open at Here East in June 2017.

GLA is now facilitating a cluster plan with clear benefits for the fashion sector and for the London communities in which it sits. The proposition for an East London Fashion Cluster (ELFC) has been arrived at in consultation with industry and local partners. It will work in partnership with industry, education and local authorities to address the structural challenges and information failures that limit productivity, investment and growth in many fashion businesses. It aims to accelerate the growth of the fashion sector in East London; secure the supply of local and graduate talent and focus the role of education, research and knowledge exchange on innovation and creative inputs.

There is an opportunity here to demonstrate ‘smart specialisation’ – reimagining London’s fashion sector as a globally significant digital manufacturing cluster that outcompetes other cities, increases high value employment opportunities and drives inward investment.

The challenge of building and sustaining a productive, high-growth and job-creating fashion sector in London is to increase the absorptive capacity for innovation across

all parts of the fashion supply chain. To achieve this, ELFC will harness London’s capacity as the knowledge and technology capital of the UK to its global reputation for excellence in fashion design and creativity. This will be achieved by increasing knowledge exchange both between fashion businesses and with other technology, creative and business service sectors. It will focus on the potential for interdisciplinary innovation and growth in fashion in East London as a way to multiply the opportunities for skilled employment and increasing wealth for its citizens.

Led by industry and incubated within UAL, the East London Fashion Cluster will represent businesses from every sub-sector of the UK fashion industry. ELFC will offer the unique combination of a dedicated world class hub for fashion education, design, business and technological innovation within an established cluster of educational, technology and cultural institutions.

The incubation of new companies, business models and support for innovation in products and services that result will emphasise that the design and creative inputs of fashion, and its huge global reach, are as much a driver of innovation in the development of new products and services as science and technology. This creates the opportunity to reimagine the fashion sector in London as a creatively-led digital manufacturing cluster; which in turn will help redefine it as a source of new opportunities for investment.

ELFC will protect, grow and project London’s reputation as a global fashion capital. In the process, it will initiate a model for change with the potential to transform the competitiveness and productivity of the fashion and textile industry in London and across the UK to allow the sector to be properly valued as part of a 21st century knowledge

economy. The partners have already begun to sound out regional partners to see if there is an appetite for a national sector / industry plan.

ELFC will coordinate and signal the different offers of specialist business support, skills development, network capability and funding available across East London. In doing so it will help provide fashion businesses with the workforce, premises, R&D capacity and working capital needed to retain talent, secure local growth and identify and exploit new intellectual property to produce the new products needed to compete in international markets and to ensure the sustained growth and profitability of the sector.

1.1 Vision Statement for ELFC

‘A cluster where fashion, technology, business and education meet. Where companies compete to out-innovate each other; where they collaborate to turn heads, all over the world.

A cluster that enlivens our culture and expands our economy. And builds on our industrial heritage and the Olympic legacy to bring new life to London.

The East London Fashion Cluster will bring together manufacturers, surface decoration textile studios, garment technology labs, designer showrooms and ateliers, digital creative agencies, journalists, stylists, media labs, technology providers, and entrepreneurs.

As the distinction between technology, engineering and creative sectors becomes more blurred the potential becomes even more exciting. The intersection between these disciplines could reinvent the future of retail or take more UK brands into the smart materials market.’

The East London Fashion Cluster: Refashioning East London. Revitalising the UK

London College of Fashion, 2016

Its aim is to re-establish London as the World Creative Fashion Capital, reinforcing its global reputation for creativity through innovation and investment in the following way:

‘Young designers and new, younger fashion consumers interact through ‘omnichannel’ retail experiences, playing to London’s strengths in both creativity and digital industries.

‘Increased collaboration between fashion designers and other creative and tech agencies transforms the sector’s relationship with external investors, releasing capital for further

innovation and growth.

‘Bolstered by the presence of world-leading resources to support technical and market innovation, London undergoes a creative fashion renaissance that cements its position as the world’s Creative Fashion Capital.’

Image Description: A rendering of a vast warehouse space. The warehouse spans across two floors and has large windows along the top of the walls and the ceiling. There are people milling around.

2. Strategic Case

2.1 Introduction to the Commission

London is one of the world’s acknowledged ‘fashion capitals’ – alongside Paris, Milan and New York. This is a huge, export-driven sector of regional, national and global importance, but one that is sometimes perceived as an esoteric and ‘cottage’ industry; and one whose importance has arguably been subsumed within discussion of the wider ‘creative industries’ in a policy context in London.

London has an international reputation for cutting edge design – reflected in the fact that three of the world’s top five fashion schools are located in the capital1/, with a strong

international element: two-thirds of LCF fashion design students are non-UK nationals. There are twenty higher education institutions offering fashion design courses in London.

Historically, inner East London was home to ‘the rag trade.’ The ‘move East’ of London’s creative industries, a trend accelerated in recent years by rising property prices in the West End and the development of Tech City, began fifty years ago as photographers, advertising agencies and other creative services began to explore warehouses and lofts in Clerkenwell and Shoreditch as a source of cheaper accommodation close to their fashion clients in the East End. That shift has been instrumental in London’s emergence as the fulcrum of the UK’s knowledge economy. East London now benefits from a blend of deep specialisms and global market penetration in finance, technology and creativity; attributes that can be recombined with centuries of heritage craft to produce new products, new processes and to reinforce the role of London as a global fashion hub.

2.2 LCF as a Catalyst

‘It is as important for a region to have a strong story to tell about innovation (in order to attract the necessary mass of new inputs to achieve it) as to have a clear policy to support R&D.’

Charles Leadbeater

Global markets demand innovation. The relocation of LCF, its 5,700 students and three schools (Fashion Business School, School of Design & Technology and School of Media

& Communication) to an Educational / R&D hub, the Cultural Education District (CED) on Stratford Waterfront, will catalyse development of an international hub for design andfashion technology, and retail innovation. It provides East London with a great ‘story’ for the global fashion industry.

An £800 million public-private partnership, CED will transform the environment for fashion innovation in the UK. The short-term benefits of the relocation of LCF, alongside University College London, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and adding to the existing presence of education and research institutions on Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park including Birkbeck, of Loughborough University London (LUL), Here East, BT Sport and Studio Wayne McGregor, will have a multiplier effect on the rest of East London. In the process it will underpin the status of London as a creative world fashion capital and act as the beacon of a new Thames Gateway Production Corridor.

LCF’s presence will be both a physical representation of the scale and ambition of London’s fashion industries and a hub for their global expansion. And where LCF has led, others will follow. LCF will provide businesses with access to emerging technologies, attracting investment from fashion and technology companies (and new investors) with the scale and infrastructure to move quickly into new markets that will in turn create opportunities for fast-moving and innovative SMEs. The offer will encourage more of the thousands of fashion students who graduate each year in London to remain in the city, confident that they will enjoy a wealth and range of opportunities that match and go beyond those available to them in other ‘fashion cities’ worldwide.

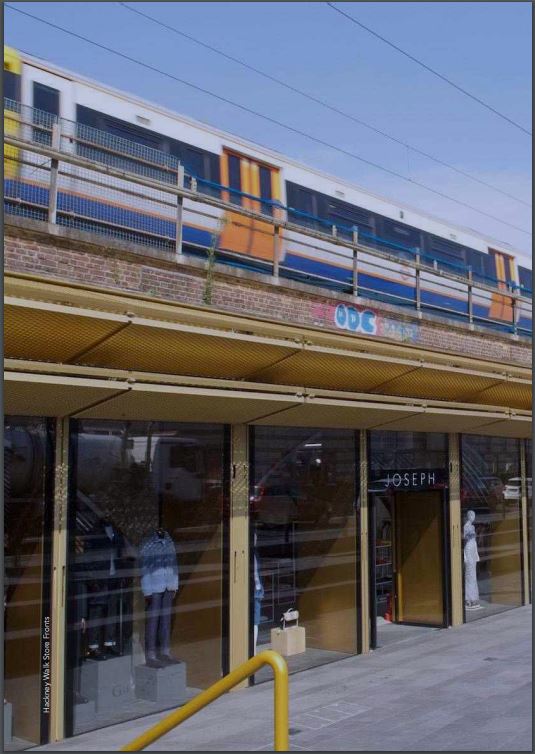

Image Description: Hackney Walk Store Fronts. An overground train passes by overhead. The store surrounds are yellow with large windows showing mannequins. One of the shops is JOSEPH.

2.3 Proposals for an East London Fashion Cluster

Proposals to establish a dedicated organisation – ELFC – to coordinate fashion sector initiatives and communicate them to industry present an opportunity to look at whether the fashion sector in London is meeting its global potential.

To make the case for ELFC we need to reflect the discrete economic, structural and reputational factors that afford London the status of a world fashion capital, and indicate where there may be barriers to growth. This will take into account:

− Current economic performance: size and output of the sector, structural factors affecting its growth

− International reputation: London Fashion Weeks, major fashion brands, export performance, the penetration of UK fashion design, manufacturing and services in international markets

− Heritage of craft skills, design and high-end fashion manufacturing expertise in East London ‘core’: Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Newham

− Wider effects – how could that transformation result in inclusive growth in the Olympic Park and surrounding areas of East London and the Upper Lea Valley?

The strategy aims to:

− Create the right business and educational conditions for East London to become the UK and Europe’s leading fashion district

− Stimulate the individual capacities of companies and institutions to create new possibilities, make new connections and tell a collective story

− Act as exemplar for sector development activity across London − Provide the hub of a network of UK fashion clusters

2.4 Rationale for Fashion

Fashion is a major global industry. The global apparel market is valued at between US$2.4 trillion2/ and US$3 trillion and accounts for 2 percent of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). 57.8 million people are employed in clothing and textiles worldwide – 24.8 million of those in apparel manufacture.3/

This is a huge, export-driven sector of regional, national and global importance, but one that is sometimes perceived as an esoteric and ‘cottage’ industry. The direct value of the

UK fashion industry to the UK economy is estimated at £28.1 billion – twice that of the automotive or chemicals industries. Fashion’s total contribution to GDP is more than £50 billion – equivalent to 2.7% of UK GDP.4/

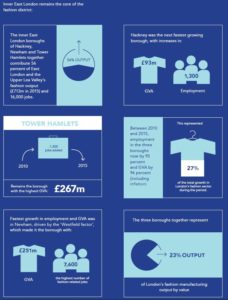

Estimates of employment in fashion in the UK range from 555,000 (Fashion United) to 880,000 (BFC/ Oxford Economics 2016). Although retail makes up the largest proportion of this, that sub-sector includes a host of strategic, management, supply chain and design roles as well as the staff within high street stores. In the UK, ‘the High Street’, in the form of large, vertically integrated retail concerns, dominates the fashion landscape – we explore the implications of this in more detail below. Fashion’s value chain covers education, design, manufacturing, distribution, textiles, wider creative, media and marketing service sectors and links to innovation in physical and online experiences, materials and technology (see Figure 1, below).

London is not only the creative and commercial centre of the UK’s fashion industry; it is one of the world’s acknowledged ‘fashion capitals’, renowned for the originality of its design.

2.5 Definition of Fashion Industry

Our definition of the fashion sector is based on the methodology developed by Oxford Economics for the British Fashion Council’s Value of Fashion report:

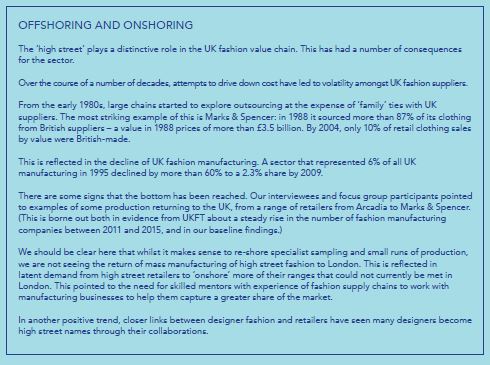

The role of the High Street in UK fashion

High Street retailers play a central and critical role in the UK fashion industry. Their influence, and price-driven competition between domestically-owned household names such as Arcadia (Top Shop), John Lewis, Marks & Spencer and Next, along with foreign-owned groups such as Inditex (Zara), shapes the UK fashion supply chain. This means that London as a fashion capital is structurally different from other centres, such as Milan and Paris, where fashion and luxury goods labels – and the major conglomerates that own them, such as LVMH, Kering and Richemont – are the major driver of trends and demand.

An export-led sector

Although separate figures for London are not available, UK textiles and apparel exports were worth £8.5 billion in 2015, up from £6.2bn in 2010. Apparel exports, with strong growth in Asian and North American markets increased to almost £5.8bn – a £2.1 billion (37 percent) increase on 2010.5/

In comparison, only 6% of the value of UK fashion retail sales is domestically manufactured.

2.6 Global trends

Trends

There are a number of ‘macro’ inluences on the strategy:

− Uncertainties in the external environment

− Emergence of new markets

− Changing patterns of consumer behaviour

− Physical and online retail pulling innovation through the fashion supply chain – whether through brand management, digitisation, channel convergence or sustainability

Fashion is a global business

Analysis of current trends identiies a number of key international markets:

− Established trading partners in North America and Western Europe

− Developed and innovative fashion markets in Japan and South Korea

− Emerging nations of China and India

− Growth in ‘megacities’ with populations of 25 million or more across Asia, Africa and South America

− ‘Gateway’ markets and potential collaborators in other emerging fashion cities such as Dubai

Digital disruption, converging platforms, diverse audiences

Digital technologies reshape markets and value chains for fashion content and information, leading to an opportunity for innovative businesses to create value added services, applications and products. ICT forms the enabling element that brings to market these services, applications and products across all sectors through production, distribution and e-commerce.

International studies reveal changing patterns of consumer behaviour. The response of ‘physical’ and online retailers pulls innovation through the fashion supply chain, and drives the creation of new business models for brands and designers. Consumers now engage with a mixture of physical and online retail environments. These vary from dedicated resource – high street and independent retailers and online platforms such as Asos, Boohoo and Farfetch, all targeted on discrete market sub-sectors – to other social media platforms that now represent an important part of the ‘real estate’ for fashion retail: eg Pinterest, Instagram hashtags.

As much as a physical product, fashion is now part of the ‘experience economy’. Consumers – particularly younger ones – expect online and high street retail environments to reflect one another, and to see new product each time they visit either the website or a physical store. The increased frequency of visits is relected in a much faster cycle of new product development and launches. This means that the supply chain needs to respond more quickly and accurately to signals of consumer demand; with physical product distributed over a more dispersed range of platforms and market sub-sectors.

This convergence of online and physical ‘channels’, and of physical and digital content, disrupts the entire business model and value chain of fashion. Designers and producers need access to up to date information and sophisticated analysis of trends and demand within increasingly specialised and divergent sub-sectors of the fashion market in order to respond quickly enough to take advantage of these market signals and to move themselves up the value chain in order to become more proitable. This presents a huge challenge to the existing fashion supply chain in London, whose digital skills and use of technology are inadequate to the challenge.

Digital technology and making

Digital technologies and ‘making’ are strategic drivers for the fashion sector. The increasing influence of technology and the rise of co-working and membership model workspaces such as Impact Hubs and Makerversity is reflected in the emergence of a new generation of fashion start ups using 3D printing, big data and wearable technology. These include:

− Unmade, whose high-tech knitwear is inspired by 3D printing;

− Fits.me, an online service that takes details of a customer’s body shape and creates a 3D model to help people igure out how clothes will it their body shape without having to actually try them on in the real world, was purchased by Japanese e-commerce company Rakuten in 2015;

− Vinaya, whose Altruis X bracelet promises ‘wearable wellbeing’.

The development of London’s fashion sector is interdependent with continuing innovation in and application of software, digital technology and advanced materials technology at all levels, from education to design to production to innovation.

Leveraging East London’s digital and creative cluster

Digital content and branding are increasingly important in establishing a competitive – which, for UK designers means international – market presence. (UK produced fashion currently represents only 6% of the total value of UK fashion sales.) The need for collaboration with creative and digital marketing agencies to create this ‘omni-channel’ customer experience goes far beyond marketing and PR for ‘traditional’ stores and twice-yearly seasonal collections. Continuing adoption of digital technology and development of a range of software skills across the supply chain is essential to growth and sustainability of the fashion industry.

Whilst they represent part of the competition for space and talent for the fashion industry, the growth of TechCity and the resulting agglomeration of creative services businesses and digital agencies are also an opportunity and a potential model for development of the fashion sector. Designers and producers can beneit from proximity to their expertise in creating the technology and assets to drive growth through business models in which platforms for manufacturing and distribution are converging whilst market sub-sectors are diverging. In the process, this engagement can help address digital skills gaps in fashion.

Innovation on the high street

Not all retail innovation happens online. High Street stores recognise that the remaining cost savings to be driven out of ‘offshoring’ are marginal – but in a time of soaring business rates and inlationary pressures are still trying to ind ways to reduce costs, whilst competing with online platforms. The case study below illustrates one way in which major retailers are adopting ‘omni-channel’ strategies:

The resulting smaller environment may feel more like an independent store, with a more ‘curated’ approach that could generate demand for ‘affordable quality’ and leading-edge pieces that could favour independent UK designers.

World Class Skills

“The creative industries now probably involve greater complexity, and greater management input, than any traditional sector. They are the antithesis of ‘Fordism’ – traditional mass production for a uniform consumer market – and, increasingly, the focus of large-scale capital investment. This suggests that important as are creative industries outputs – creative products – what may in the long-term be most notable are the creative industries processes involving innovation and customisation. Creative industries inputs – notably creative labour itself – may be the key factor.”

(GLA, 2004)

London has long understood that availability of a skilled workforce is the key factor in inward investment decisions in this sector. In order to compete in a global market for talent, London will have to attract and retain individuals with high level qualifications and relevant specialist skills. In this, the region’s Higher Education Institutions will play a critical role.

However, the sector is now seeing indications of shortages in essential creative, production and technical disciplines – notably around specialised manufacturing skills. – that are only likely to be exacerbated by the threat to free movement of labour raised by Brexit. At present, London is a global entrepot for fashion design, with 67% of LCF’s fashion students arriving here from other countries. Many graduates are attracted by the greater breadth of career opportunities currently available to them in London, including the potential to set up their own businesses. Skills developed in London are also in demand from other established fashion capitals, and from fast-growing clusters in emerging markets such as Dubai.

Changing workplaces

The fashion hub at Hackney Walk is an example of commercial development that is looking to encourage more lexible use of spaces to support the growth of new fashion brands. Increasing utilisation of pop-up stores and shared workspace helps reduce cost and risk for new designers – whilst also giving them a foothold for more experimental collections in the midst of a retail environment anchored by major brands such as Burberry and Nike.

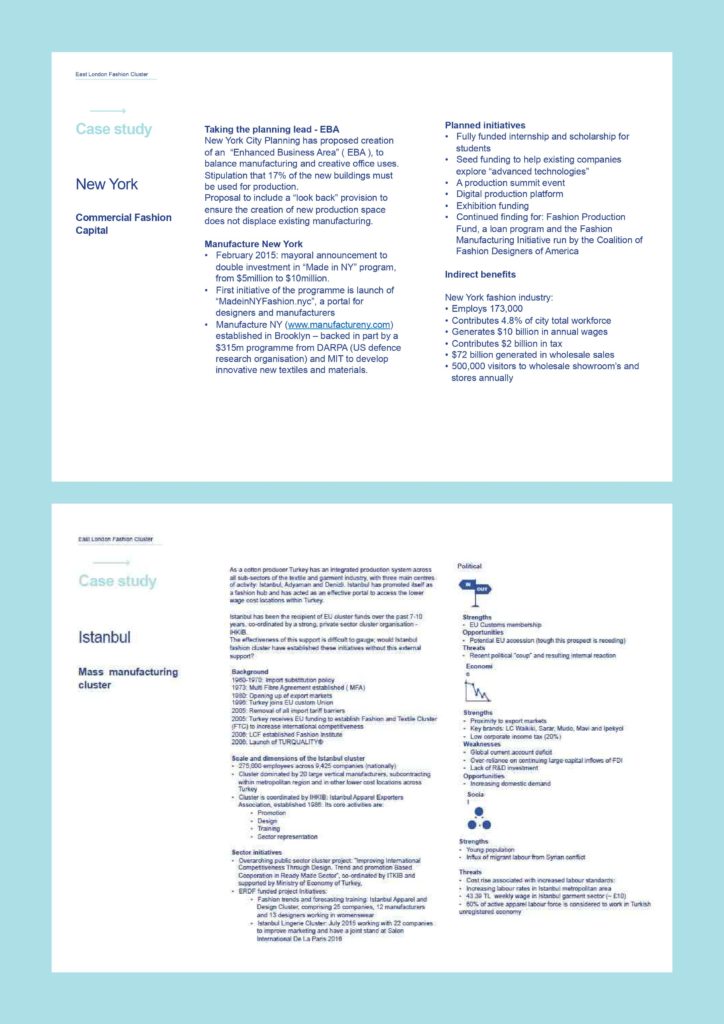

Competitor cities

Rival cities are not resting on their laurels, of course – major fashion cities are all seeking to grow their share of the global market. New York is directly investing large sums at city and national level, and leveraging signiicant private investment in the process, in attempts to grow an innovative fashion design and manufacturing cluster. Dubai is investing heavily in its Digital Design District, seeking to identify itself as a global hub for design-led IP and retail innovation. Istanbul is accessing EU funding to move their apparel and textile sectors away from the associations of being a ‘low cost’ producer and up the value chain through increasing the quality and design input of their end product. And cities like Milan and Los Angeles, which in their different ways demonstrate the beneits of decades of industry-led coordination of a vertically-integrated fashion sector, are seeking to adopt the benefits of new technology and a start-up mentality from their neighbouring tech clusters.

At the same time, low-cost producers in emerging economies are facing pressures including rising commodity costs, rising middle class staff costs and increased scrutiny of labour practices and supply chain sustainability. Their response is to steer a course away from ‘red oceans’ of intense competition for low cost production. The desire of the Chinese government to increase the design content of locally manufactured goods, and efforts of cities like Istanbul to capture more of the added value within the garments they produce, are a conscious attempt by competitors to move up the value chain – a potential competitive threat to the perception of London as the fashion capital that adds most value through design.

Ethical and sustainable fashion

Concerns around the sustainability and work conditions associated with ‘fast fashion’ have led to the emergence of a new type of consumer type, increasingly conscious and inquisitive of where and how their clothes are made.

This is relected in different forms across the fashion supply chain:

− Specialist brands such as People Tree, producing Fair Trade and environmentally sustainable clothing

− Mainstream brands including Monsoon are keen to promote ‘ethical trading’ – Monsoon has its own ethical compliance team and a Code of Conduct which sets out minimum requirements on working conditions, pay and employment rights for its suppliers;

− Online fashion brands have sought to delect criticism of the negative environmental and social impacts of ‘fast fashion’ by creating niche brands, such as ASOS Eco Edit, that promote ‘ethically conscious’ British brands, craft goods and ‘upcycled’ vintage clothing under a ‘sustainable banner’

Disciplines

− The trends above all highlight the global and interconnected workings of the fashion industry. That emphasises the need for all elements of the fashion sector in East London to come together in a concerted way to address challenges and market opportunities. Many of these require a hybrid response – simply addressing technology, design, brand, or manufacturing in isolation will not provide a solution.

− McKinsey6/ identiies three disciplines in which fashion companies need to succeed:

− Global-local brand management – the internationalisation plan within the strategy depends on the ability of London and its fashion companies need to clearly differentiate their offer, to re-invest in the brand value of London as the world’s creative fashion capital.

− New shopping experience – changing the concept, design and even location of stores (cf John Lewis case study above)

− Multichannel strategy – our illustration of omnichannel retailing (below) highlights some of the behavioural changes that result

Together, these challenges clearly demonstrate that fashion companies need to expand their view of the skills they need. Smaller companies, in particular, should not necessarily expect to acquire the capacity to directly employ all the specialist skills required; but they will need better information about capacity available in education, in suppliers, in competitors and in service companies to help them thrive in this multichannel environment.

Section 2 Footnotes

1/ http://fashionista.com/2016/06/best-fashion-colleges-2016

2/ McKinsey & Co (2016). Global Fashion Index http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-state-of-fashion.

3/ Fashion United (2016). https://fashionunited.com/global-fashion-industry-statistics

4/ British Fashion Council and Oxford Economics (2016). The Value of the UK Fashion Industry

5/ UKFT (2016). Compendium of UK textiles and apparel manufacturing data.

6/ McKinsey & Company and The Business of Fashion (2016). The state of fashion. http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-state-of-fashion

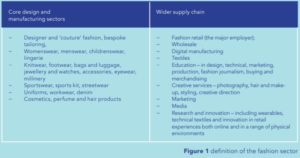

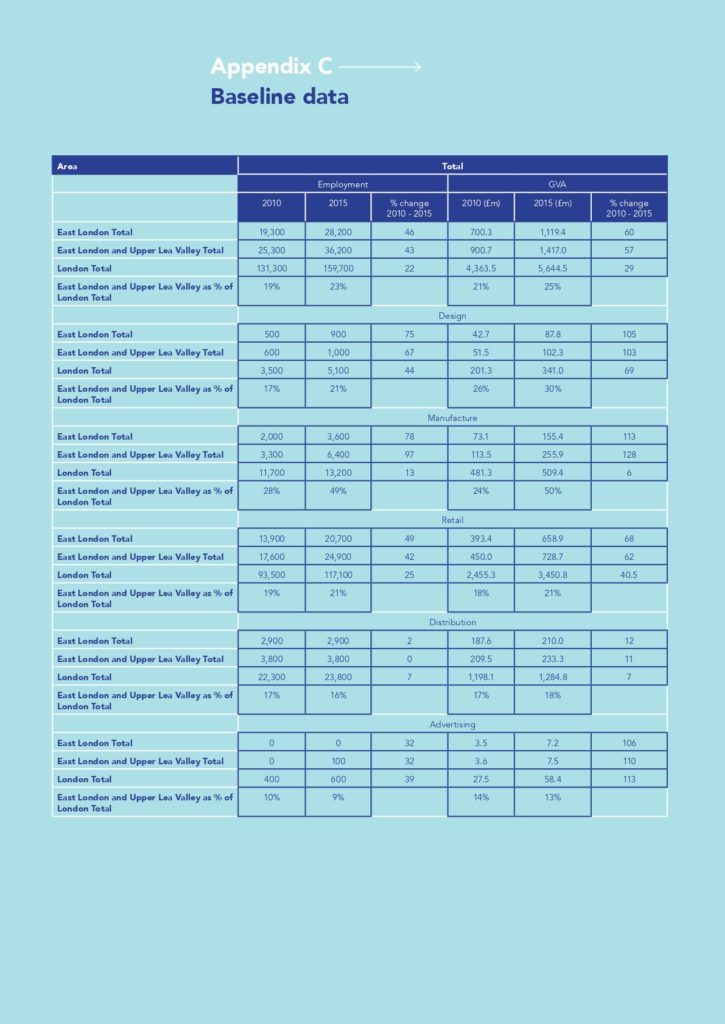

BASELINE DATA

Image Description: The exterior of Anya Hindmarch on Hackney Walk. The building is painted black with white and gold lettering and accents.

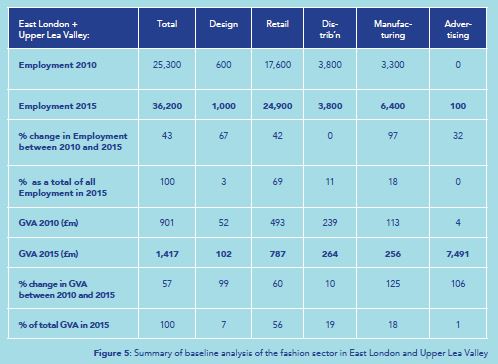

3.1 The fashion sector in East London and Upper Lea Valley Our review of employment

Our review of employment and output statistics, supports anecdotal evidence of growth in the fashion sector in East London, led by retail employment at Westield, the emergence of Hackney as a design powerhouse and a re-emergence and reshoring of value-added manufacturing across East London and Upper Lea Valley.

Key Findings

Findings of the study confirm that if London is to continue to support world-leading creative designers and to grow fashion as a broadly- based employment sector including a sizeable number of jobs in manufacturing, there is an urgent need to build capacity, and promote innovation and resilience across the whole value chain.

Fashion contributes over £1.4 billion in GVA and 36,000 jobs to the economy of East London and the Upper Lea Valley.

− There is a clear concentration of Specialist Design Services in East London, with strong Manufacturing growth in the Upper Lea Valley; despite its structural challenges, manufacturing is the fastest growing fashion sub-sector, with a 94% increase in employment and 128% increase in GVA between 2010 and 2015.

− Fashion manufacturers currently lack appropriate skills for 21st century – from basic software to garment technology skills and utilisation of emerging equipment/digital fabrication methods

− Fashion Designers suffer from a systemic lack of access to finance to stem crucial gaps in cashflow, along with issues between young designers and manufacturers are strained largely due to this, and lack of practical experience

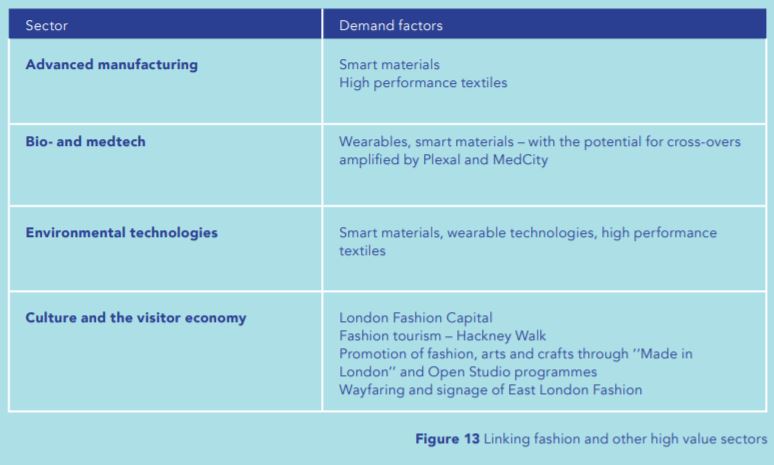

Figure 2 Summary of baseline analysis of the fashion sector in East London and Upper Lea Valley

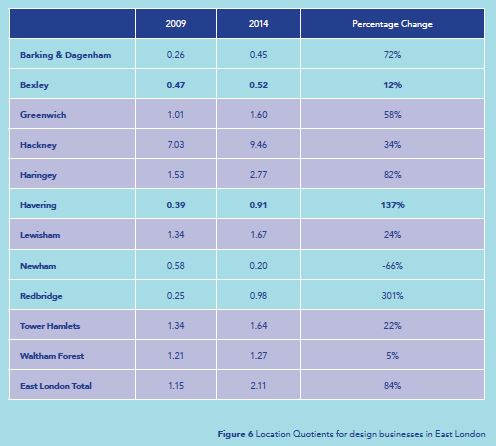

The majority of East London boroughs have a concentration of specialised design businesses. The table below show location quotients (LQs) derived from BRES data for design employment in East London. Any score above 1 (marked here in red) indicates a higher than average concentration of design-based businesses8/. We observe a pattern of increasing concentration of design business in most boroughs. Hackney’s score of 9.46 is notable.

These igures indicate a trend of increasing design capability and clustering in East London – and, as design is understood to be a driver of many other sectors, is a good indication of the potential absorptive capacity for innovation.

Strengths of the fashion sector in East London and the Upper Lea Valley

High growth sector: GVA from fashion in this sub-region grew by 57% (including inflation) between 2010 and 2015, against 29% for the sector in London as a whole.

Scale – There are 36,200 people in full-time employment in East London fashion in 12,000 businesses – an increase of 10,900 jobs and 1,800 companies between 2010 and 2015.

Resilience: Fashion in East London has demonstrated resilience in its growth during a period of turbulence in its external market environment – in particular, in the re-emergence of added-value production for high-end fashion products

Image – Hackney Fashion Hub has helped stimulate awareness of the fashion sector in East London amongst international consumers through its mix of global brands (Burberry, Nike) and independent designers.

East London is growing in importance as a location for design businesses – analysis of location quotients (LQ) for design reveal that East London as a whole has an LQ of 2.11 – more than double the expected number (where 1 represents the national average density of designers in the working population). Five East London boroughs combine high design LQs and high growth: Hackney, Haringey, Lewisham, Tower Hamlets and Greenwich. In all five, we observe increased employment in other fashion production and distribution sectors. Newham, whose growth is driven by fashion retail, is a clear outlier.

Competitive advantage – London has the highest concentration of high value ‘convergent media’ businesses (with the greatest capacity for innovation and GVA growth) across a range of activities that are adjacent to and could have a direct bearing on future development of fashion, including: software development, ‘Internet of Things’, publishing, creative services, digital manufacturing, robotics, and music.

Image Description: A white man with sunglasses on his head works at a sewing machine at Fashion Enter.

3.2 Existing support for fashion businesses

LCF runs a number of programmes to engage in R&D with businesses:

− LCF’s Fashion Innovation Agency’s objective is to harness technology to enable a wider range of products and processes and fostering design- industry relations. It plays a potentially important role in shaping the brief for a shared R&D space on CED, and in channelling dedicated challenge funds for collaborative innovation in fashion and technology.

− LCF’s Centre for Fashion Enterprise runs the Fash-Tech Pioneers Programme, a six-month incubation programme designed for technologists wanting to disrupt the fashion industry, and provides dedicated mentoring (on legal, accounting, marketing, branding, storytelling, pitching etc) to selected applicants.

− LCF is a partner in Central Saint Martins’ Innovation Insights Hub, which connects insights and ideas from creative practice to contemporary challenges to provide innovative outcomes.

GLA is also investing in capital programmes to build capacity for the fashion supply chain in East London:

− Building Bloqs, a membership-based workshop space in Meridian Water, Enield, recently received £2,700,000 of funding via the London Regeneration Fund for workshop expansion, which will include an expanded textile lab.

− Fashioning Poplar, a project initiated by Poplar HARCA, LCF and The Trampery to convert 80 disused garages on a Poplar housing estate into manufacturing space, studios, and training space for use by students, designers and ex-offenders, received £1.7m through the London Regeneration Fund.

− Hackney Fashion Hub – following the riots of 2011, the Mayor’s Regeneration Fund provided London Borough of Hackney and Hackney Walk with £1,500,000 of investment to renew and address the viability of Hackney town centre. This included work on public realm and converting the irst phase of 12 of 22 railway arches into showrooms, retail spaces and studios.

− In 2015, Albion Knit received a £100k loan to purchase a lat-bed knitting machine and pay for trainee operators, technicians and apprentices, funded through GLA’s Opportunity Investment Fund, a £3.64m fund towards workspace/commercial space activation in Tottenham.

The private sector is also offering a number of skills and innovation programmes. These are detailed in the action plan (see below), but the interest of new investors in the sector could be catalysed by the launch of Plexal at Here East in June 2017. A private sector accelerator for ‘lifetech’ companies working across a number of disciplines, operated by the team that established the successful intech incubator Level 39, Plexal will promote fashion as a channel to embed design thinking and creativity into all parts of the private and public sectors including manufacturing, business processes and public sector procurement. This has the potential to greatly expand the range and scale of the markets addressed by fashion and design thinking.

3.3 Focus group and interview findings

The discrepancies between headline growth shown in the statistical base and reported barriers to growth were explored through a series of interviews and focus groups with 20 fashion bloggers, designers, manufacturers, retailers, landlords, training providers and supply chain experts. The inputs of these experienced practitioners helped to clarify how trends observed in our desk research were playing out in the fashion economy of East London. The sessions helped to identify further opportunities and barriers to growth that

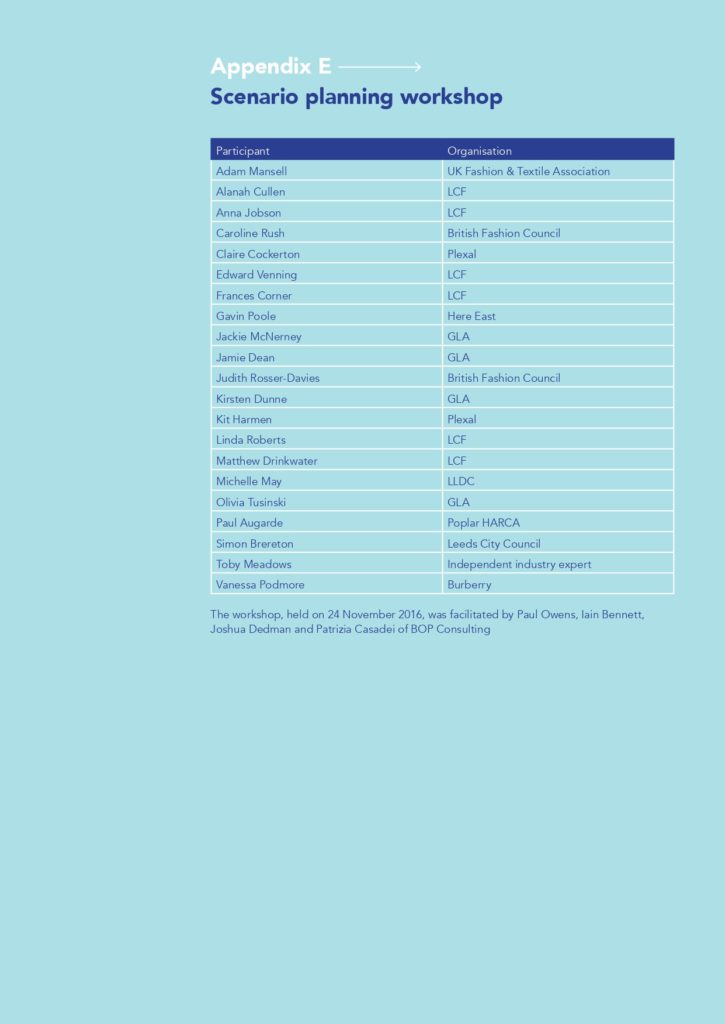

informed a subsequent scenario planning workshop, held to reine the proposition for the ELFC. (Details of attendees are attached at Appendix E, below.)

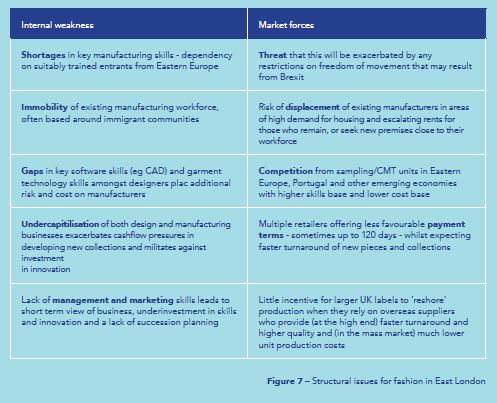

Structural issues facing the fashion sector in East London

The focus groups conirmed a number of structural challenges that are holding back latent growth potential and in the longer term may threaten the long-term sustainability of the fashion sector in East London.

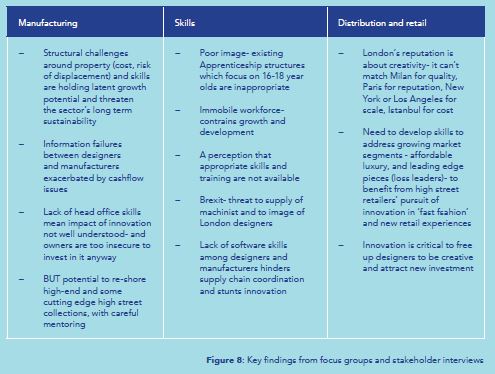

We have described how market forces and digital technology exert a particularly disruptive and volatile inluence across the fashion value chain. The table below highlights ten factors, ive internal and ive external, that result in the fashion supply chain being unable to respond to market opportunities and expose manufacturers in particular to increased risk.

Lack of garment technology and software skills

Manufacturers also complain that design graduates lack the garment technology skills needed to translate their creative ideas into inished products. This problem is heightened by a shared lack of digital skills – use of computer-aided design software among both designers and manufacturers is very low.

Missing opportunities

Poor communication between sub-sectors means that designers and manufacturers fail to work together to address new market opportunities. At present, the accuracy with which market signals are received – for example, how increased demand for ‘affordable luxury’ needs to be relected in different price points, or how high street retailers are increasingly looking to identify ‘loss leading’ innovation on rapid turnaround to add an element of novelty to increase footfall and repeat visits – varies widely not just from sub-sector to subsector and from place to place but from firm to firm.

Terms of trade and cashflow

Further barriers are created by the tough terms of trade imposed by retail clients, many of which will only pay 90 or 120 days after inished goods are delivered. Most early-career designers do not have the working capital to pay for the manufacture of the collection in

advance, leaving the manufacturer to carry the risk and manage their cashlow. As a result, many high-end ‘cut, make and trim’ (CMT) businesses are reluctant to work with new designers.

Competition from lower cost producers

This in turn leads to further leakage of demand to CMT shops in Eastern Europe and further aield that are prepared to take on more of the work of interpreting initial sketches into finished garments.

Skills shortages and concerns about Brexit

Brexit, and the threat it represents to freedom of movement for students and skilled workers coming from other EU countries is a real concern to employers. Skilled machinists from Eastern Europe, where technical colleges teach skills no longer included in the English curriculum, are an important part of the East London fashion workforce and have themselves established a number of successful CMT businesses. Uncertainties about their continuing rights to work and reside in the UK post-Brexit have led some to return to their countries of origin, and has reduced the flow of new workers. There is no immediate way to plug shortages in these skills.

Opportunities around ethical and sustainable fashion

Graduates show little awareness of sustainable design and manufacture within the fashion supply chain. This is not typically a core part of training at many universities and colleges. The Ethical Fashion Forum (EFF) also reports that people from within ‘mainstream’ fashion businesses, who feel that they are unable to influence their employers to adopt more ethical and sustainable practices, are coming to their events to seek out opportunities within ethical fashion SMEs or to get information about starting their own enterprises on a more sustainable basis.

Made in London?

There was some debate within focus groups, and a difference of views between sessions, about the respective merits of promoting a ‘Made In London’ brand. Some questioned whether the supply chain could deliver the consistent quality required to deliver this as a

brand in the market; and whether manufacturers in other parts of the UK would be happy to have their goods labeled in that way. The discussion highlighted the reality of the supply chain in which a finished garment may be assembled from a mixture of international inputs and processes. Others pointed to a pragmatic approach to branding a collection – ‘you may make the jacket in London, but the shirt could come from Portugal.’

The future is creative

Our focus group members – particularly in the retail workshops – were clear: London fashion has an international brand that reflects freedom of expression, expression of individuality, quirkiness, experimentation and youth.

Our focus group on fashion retail and distribution was realistic about the issues to the retail sector and structural challenges, in the shape of increased premises costs, that have resulted in the closure of large numbers of independent retailers; and the fact that this has resulted in fewer opportunities for independent designers.

But they were clear about the future direction.

− London’s reputation is about creativity – it can’t match Milan for quality, Paris for reputation, New York for scale.

− The collapse in the number of independent fashion retailers means that designers have to deal with high street retailers and international distribution at an earlier stage in their development – which increases the risks of failure.

− Better information about global fashion trends, increased technical skills and greater understanding of manufacturing and supply chains can help London’s designers to address growing market segments – targeting affordable luxury and leading-edge pieces (loss leaders) to help the high street retain interest in its ‘fast fashion’.

− In order to harness these market opportunities and address skills gaps, more needs to be done to harness the potential for interdisciplinary working between fashion and other creative and technical sectors.

− The UK industry and individual businesses within it need a technology road map in order to understand how to commit development resources and capital expenditure to digital skills and technology – like all other business planning, it is an essential precursor

to growth. ELFC has a critical role in increasing the number and speed of collaborations between industry, innovation institutes within HEIs and the experience of acceleration and R&D programmes in other creative sectors to agree the terms of reference for this significant piece of work.

− Innovation is critical to free up designers to be creative and attract new investment.

3.4 Competitive and international perspective – fashion capital case studies and comparators

Image Description: A shot from above at Fashion Enter shows a dozen works spaces with people working on garments.

In embarking on any strategy for the fashion cluster in East London, it is important to understand the different ways in which the effects of this increased volatility, not just in the UK but in global markets, work their way down through the supply chain. It is also important to be objective about the strengths and weaknesses of the fashion sector in East London, both in absolute terms and in relation to its major international competitors.

With that in mind, we looked at a handful of international comparators to see what lessons, if any, public intervention in fashion held for London:

− World fashion capitals such as New York and Milan;

− Major manufacturing hubs in Istanbul and Los Angeles that, from a value chain perspective, represent contrasting approaches to building a vertically integrated fashion sector;

− Competitors from emerging economies, such as Dubai, that are looking to compete on the basis of added value and innovation, rather than on the more traditional entry route of low cost;

In other European cities – such as Amsterdam and Antwerp – the public sector has taken a strategic approach to intervention in the fashion sector, backed by investment in international marketing to establish themselves as a fashion capital.

We focus on two studies here:

− Los Angeles, which offers an example of a vertically-integrated fashion design and manufacturing supply chain

− Milan, which demonstrates the importance of retaining craft skills and variety in the fashion supply chain

Notes on New York and Istanbul are contained in the technical appendices.

Case study 1 – Los Angeles: can London offer a vertically-integrated supply chain?

Los Angeles is an example of a cluster that has leveraged structural opportunities through an effective, B2B cluster organisation (California Fashion Association), founded in 2015 and funded by subscription.

Los Angeles enjoys several advantages due to its location:

− Access to cheap power and raw materials

− Access to large and (until recently) comparatively low wage workforce – average machinist wage in California in 2014 was $11.54 per hour

− Los Angeles has one of the densest concentrations of apparel manufacturing industries

– the LQ of its womenswear sector is over 17!

− LA is the USA’s #1 port, offering easy access to global markets in addition to the domestic market of 300 million consumers

− Proximity to a significant source of IP from the film and entertainment industry – which it licenses and leverages alongside its own premium ‘Made In California’ brand – offers competitive advantage and opportunity to increase margins

− Scale – over 110,000 workers are employed in apparel manufacture in 6,000 companies; total turnover of the garment manufacturing sector in 2015 was $13,650 million (Hoovers, 2015)

− Maturity – half of the companies in the cluster are over 25 years old; more than 1,500 turn over at least $1m per annum

− Los Angeles offers different models of vertical integration within different markets:

− Integrated manufacturers: design and make their own clothing brand, and make products in their own manufacturing plants and in those of independent contractors.

− Licensees: may or may not be involved in the product development process, but “rent” their brands to producers of fashion products

− Contract manufacturers: may have long-standing relationships with designers, or may use brokers to generate new business, Contract manufacturers win business on their ability to deliver on-time and on-cost. The manufacturer placing the order typically owns all the raw materials.

Although Los Angeles is not regarded in the same league as London or New York in terms of creative fashion design, it has been astute in understanding which aspects of its brand will still attract a premium for some products – eg, jeans ‘Made in California’.

LA is a ‘true’ cluster, in terms of scale, interlinked support and some common goals. Although less ‘prestigious’ than the ‘world’ fashion cities, it has a unique heritage and cultural position, which thus far has been exploited by the cluster, growth has occurred with no public-sector input, but through organic growth based around resilient companies who have maximised the local trade agreements.

The main lesson for ELFC is that public support can come in many forms – trade agreements, particularly NAFTA, are at the core of the cluster’s success. However, despite recent encouraging developments in ‘onshoring’ production, London is unlikely ever to house manufacturing on that scale; so another point – the way in which LA manufacturers successful leverage proximity to other sources of IP, in the form of entertainment brands – is one that could be explored in development of London’s presence in important, relevant and growing sub-sectors such as sportswear.

Case study 2 – Milan: the importance of retaining craft skills and variety in the fashion supply chain

The way in which Milan has historically paid close attention to quality across the whole of its fashion supply chain enabled its small and medium-sized craft manufacturing businesses to quickly switch their focus to high-end specialist manufacturing in a strategic response to increasing outsourcing of mass produced apparel to low cost countries. The Milanese industry differs from the UK model in that it is dominated by large maisons (fashion labels) rather than by multiple retailers. These maisons are physically clustered together in the city centred and surrounded by a supply chain of highly skilled producers extending beyond the boundary of the Metropolitan district. This proximity reinforces both opportunities for a shared commitment to quality, reflected in a proposal to certify suppliers. It also benefits shared involvement in innovation and the responsiveness of the supply chain to changing patterns of consumer behaviour.

The large fashion houses recognise the interdependency of the cluster and the strategic benefits of keeping (in particular) high-end production within the local supply chain. This means that they actively seek to support small craft producers and specialist manufacturers as a way to retain variety and diversity of supply within the cluster, preferring this to the option of low cost outsourced production in order to retain transparency of the production process and control over the quality of the end product.

Milan’s fashion manufacturing and design sectors stand for quality in the minds of consumers and designers alike, and the industry works to ensure that this is reflected from top to bottom of the supply chain. Government, Trade and Private sectors have collaborated to ensure that this simple but powerful message has been heavily promoted around the world for over 50 years. This has resulted in:

− Immense added value in consumers’ minds around the world for the “Made in Italy” label

− Strong global reputation as a “Big Four” fashion capital

Despite the reshoring of some high-end production that has taken place during this decade, London, like Milan, is no longer a competitive location for the production of mass or entry level goods. This has led some suppliers to pursue the same strategy as those in Milan: a greater focus on high level production and finishing as a specialism. But the sector lacks coordination and management often lacks the skills or working capital to address growth markets, such as the high growth ‘affordable luxury’ segment, that require much greater levels of skill and responsiveness from the manufacturer.

Despite its very different supply chain relationship with high street retailers, ELFC would support London’s specialist and added-value production companies (through addressing information failures to improve coordination within the sector) to develop the potential to:

− Build upon East London’s long history and reputation for the making of luxury goods

− Exploit proximity and links between local manufacturers and designers

− Address information failures by opening up the wealth of manufacturing knowledge in CMT, artisan, leather and textiles workshops for young start-ups and designers

− Improve coordination by promoting networking between suppliers – not as a ‘nice to have’, but an essential way to maintain the integrity of the supply chain

Lessons for ELFC:

− Actions of fashion labels to support diversity in the supply chain enhance the sustainability and competitiveness of small manufacturers specialising in sampling and CMT (‘cut, make, trim), essential if London is to retain capacity to produce the small quantities needed by independent designers.

− There is an opportunity for established labels to work with UK manufacturers to develop new and responsive systems and supply chain relationships, including through employment of experienced intermediaries and mentors.

− Diversification of manufacturers which traditionally specialised in one craft skill (eg, leather goods) could enable them to undertake production of whole ranges for highend fashion labels.

− Closer integration and increased knowledge exchange between different levels of the supply chain leads to greater confidence in investment in skills and innovation amongst smaller producers.

− Milan’s reputation for quality is central to its branding as a World Fashion Capital. London and the UK hasn’t strategically promoted such a singular definition within its fashion sector.

− Future proofing London’s manufacturing base is key and as in Milan ‘networking between specialist suppliers is paramount for survival.

− There is an opportunity for ELFC to play a central role in defining London as the world’s ‘Creative Fashion Capital’ and take a lead from Milan/Italy in heavily promoting this globally.

3.5 Analysis

Fashion located in East London because it combined cheap accommodation with easy access to market. It was a catalyst to the ‘move East’ of creative industries that drove the development of a high value knowledge economy in the City Fringe. Ironically, that success has now created demand for premises for housing and other more valuable economic activities that presents a huge risk of displacement to existing fashion businesses.

Another factor in the success of fashion in East London has been access to skilled migrant labour, which has been drawn to the area by the same combination of low cost accommodation and economic opportunity in a trend that dates back centuries. Immigrant and transient groups form continue to form a significant part of the fashion workforce, and the same pressures now threaten their ability to remain in the area.

However, the growth of knowledge economy hubs such as TechCity and the resulting agglomeration of technology, finance and a workforce with new kinds of skills now offers fashion in East London an opportunity for growth through a focus on higher value products. This in turn has the potential to benefit some of the most deprived communities in London through new jobs and higher wages.

The baseline data supports the strategy of creating production corridors in East London and Upper Lea Valley as a source of new jobs and GVA – and the success of fashion manufacturing could be a ‘beacon’ for wider policy initiatives to address retention of industrial premises.

All this is happening despite market volatility and the evidence that there is plenty of room for improvement in information flow, skills development, innovation and promotion.

This isn’t a ‘zero sum’ game: promoting clustering of fashion, technology, business and education extends the opportunity for other industries to address a $3 trillion global market.

This is an opportunity to demonstrate ‘smart specialisation’9/ – reimagining London’s fashion sector as a globally significant digital manufacturing cluster that outcompetes other cities, increases high value employment opportunities and drives inward investment.

Effectiveness of public sector intervention

How does the experience of other cities help shape the proposition for London?

− The option to invest large sums of EU money – in the case of Antwerp, to brand itself as a fashion capital and tourist destination; in Istanbul, to develop capacity to vertically integrate its textile and fashion manufacturing sectors – is no longer available to London. But the opportunity to better coordinate marketing of fashion as part of the city offer of visitor economy and inward investment – as observed in the ‘I amsterdam’ campaign – is picked up in proposals for year-round promotion of ‘London Fashion Capital’, building on existing high profile campaigns such as London Fashion Week and the ‘Fashion is Great’ trade and investment promotion coordinated by British Fashion Council and UKFT with the Department for International Trade.

‘Manufacture New York’ (www.manufactureny.com) offers a model of incubation and business support integrated within new manufacturing capacity, seeded by a $3.5m investment from NY City Hall.10/ The major investment, however, is a share of a $315m innovation project by US Department of Defense and MIT to promote innovation in textiles.11/ Our proposal for a Fashion Manufacturing Hub borrows from the model, but is more organic in scale; other funding initiatives will address the need for fashion to be better positioned to be in receipt of equivalent (if more modest) Government innovation funds available through Innovate UK.

− Dubai’s ‘D3’ (Dubai Design District) is another attempt by the Emirate to build a creative cluster from scratch. Previous efforts – Dubai Media City and Dubai Tech City – have had limited impact on their respective sectors. Dubai’s fashion reputation is linked to its status as a visitor destination, but its approach to fashion, eschewing manufacturing altogether in favour of a focus on digital innovation in garment design, branding, online and physical retail experiences, reflects our findings about the technological drivers of growth in an ‘omnichannel’ retail paradigm.

− Milan and Los Angeles, in different ways, emphasise the importance of a strong industry-led body to coordinate sector development and lobbying. Again, this is about providing an effective interface between fashion and the public sector in the way that ELFC sets out to do.

Case study comparisons - Cluster Support

Antwerp

− 1980: ‘five year textile plan’ saw investment of €687m, 80% of which went to Flanders, which aimed to recover the competitiveness of firms through the reconstruction of their capital, the modernisation of their production technology and the creation of 100,000 jobs − 2002: Creation of ModeNatie – putting main fashion research, training and tourism resource under one roof – part of a long term plan to brand Antwerp as a fashion capital

Los Angeles

− California Fashion Association (est 1995) – not-for-profit, subscription based B2B organisation – promotes Fashion District, organises events, manages information resource bank and links with other associations

− ‘Made In California’ attracts a 9% premium

New York

− Made in NY: $10m per annum

− Madeinnyfashion.nyc portal for designers and manufacturers

− Fully funded internships for students

− Seed funding to explore ‘advanced technologies’

− Fashion Production Fund

− Exhibition funding

Enhanced Business Area” ( EBA ), to balance manufacturing and creative office uses. Stipulation that 17% of the new buildings must be used for production.

Milan

Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana (CNMI, est 1958) working in partnership with an asyet-unnamed bank to create a resource centre that, among other things, will help young designers up their e-commerce game. Also planning training, and financial support for young designers, including a physical work space ‘hub’ not unlike the CFDA incubator.

Amsterdam

− ‘I Amsterdam’ trade and investment promotion includes dedicated creative industries/design expertise to provide advice and facilitate inward missions

− Netherlands has a strategic focus on Dutch design (as opposed to creative industries in general) in its export promotion

Dubai

− Dubai Design District (‘D3’) looking at innovation in fashion retail from a ‘smart cities’ perspective

− Water shortages mean that manufacture is impractical; so the entire focus is on retail, distribution and design using the very latest Internet of Things technology, AR, VR …

Istanbul

− EU funding to establish Fashion and Textile Cluster (FTC) to increase international competitiveness

3.6 Developing the proposition for East London Fashion Cluster

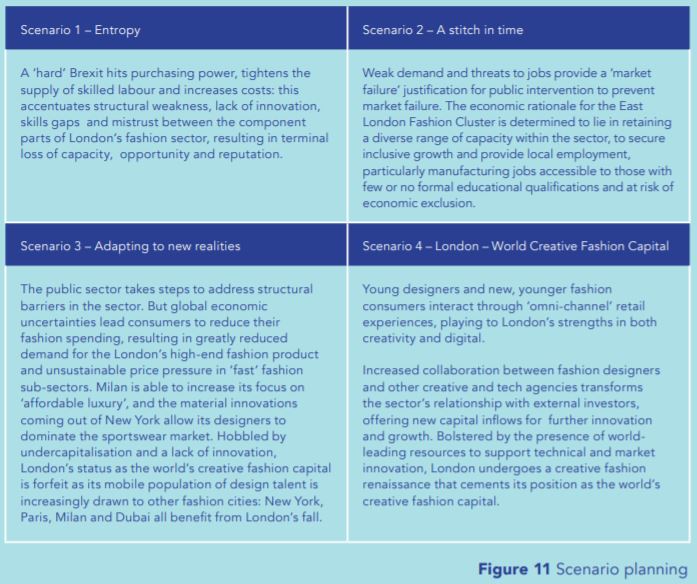

Scenario planning, involving a group of industry professionals and academics (see Appendix E, below) in a workshop setting, was used to help narrow down the strategic options and objectives for sector development, and to start to frame plans for how support might be focused. We asked the workshop participants:

− Should a focus on place/variety put more emphasis on the supply of new entrants to the fashion sector – seeking to keep rents down, etc – or on greater variety within the place – eg, higher levels of innovation, more manufacturing?

− What is the relationship between physical ‘clustering’ and agglomeration effects? Is it feasible to locate some of the cluster infrastructure in other parts of the Thames Estuary (eg Barking & Dagenham, Havering) whilst retaining the sense of place and variety?

− What are the ‘human factors’ of this cluster? How mobile is the fashion workforce (indigenous manufacturing businesses, existing design businesses and new entrants)? How could existing skills shortages and gaps best be addressed?

− Who leads? Is there a single organisation that should have a programmatic overview and coordinating role in both capital and revenue projects? Or is this ‘horses for courses’?

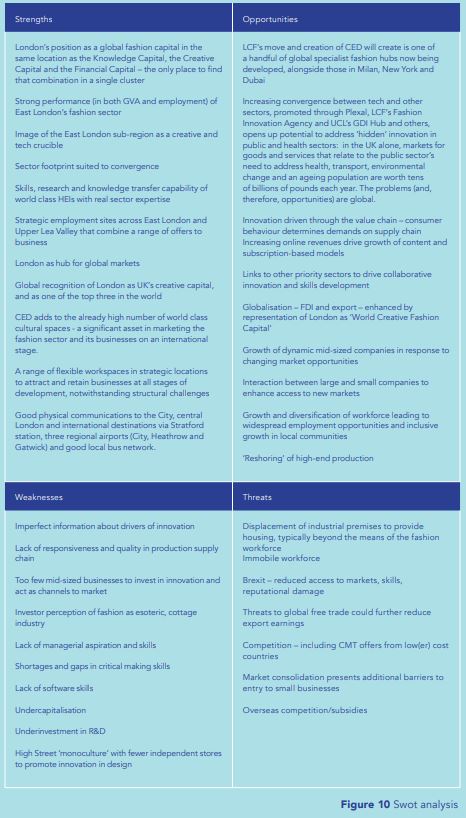

Risks in the current environment – ‘do nothing’ scenario

Analysis of the business case for any public intervention typically includes consideration of the ‘counterfactual’ – a ‘do nothing’ case. In the case of East London, the structural barriers to sustainability and growth of the sector (detailed in the SWOT analysis below) point to the need for intervention to address poor information and coordination, skills gaps and shortages, and the consequences of widespread undercapitalisation. These would be serious concerns at any time, but the uncertainties around Brexit and the sustainability of current global trading arrangements could point to an even more gloomy prognosis.

However, the planned development of CED and LCF’s move, mean that the situation for fashion in East London will change. We are careful not to describe that move in itself as a ‘silver bullet’ to address all the sector’s shortcomings and move all the barriers to its continuing presence as a widespread employment sector in East London. It does, however, allow us to calibrate both the nature and scale of the support needed by the sector, and to examine the likely impacts of different approaches.

We therefore presented a range of different scenarios of how the fashion sector in East London might respond to opportunities and threats in the political, economic, social and technology environment. Participants were presented with a detailed series of scenarios, each with their respective political, economic, social and technological implications: we summarise these in the table below.

London, World Creative Fashion Capital

The proposition that emerged from the group is one that been expressed by industry representatives in the focus groups. Without dismissing the constraints imposed by existing structural challenges and information failures that limit productivity, investment and growth in many fashion businesses, and without being complacent about the risks of falling demand and tougher trading conditions in the global economy, it asserts that the challenge of building and sustaining a productive, high-growth and job-creating fashion sector in London is to increase the absorptive capacity for innovation across all parts of the fashion supply chain.

The renaissance of the fashion sector in East London will be accelerated by its proximity to other centres of knowledge capital in Tech City, the City and Canary Wharf. East London is the only place in the UK in which fashion designers, finance, major knowledge economy hubs such as Tech City, the head offices of major fashion brands and retailers and specialist high end garment manufacturing meet face-to-face. Both incomers and indigenous businesses, start-ups and scale-ups will benefit from that proximity, which will offer ease of access to the talent, technology and capital to exploit their creativity to maximum advantage.

ELFC will trigger a significant increase in R&D activity across this geography, drawing in investment from UK High Street retailers and high end fashion labels to increase London’s capacity and knowledge to deliver profitable innovation to the fashion supply chain.

The aim is to re-establish London as the World Creative Fashion Capital, reinforcing its global reputation for creativity through innovation and investment in the following way:

‘Young designers and new, younger fashion consumers interact through ‘omnichannel’ retail experiences, playing to London’s strengths in both creativity and digital industries. ‘Increased collaboration between fashion designers and other creative and tech agencies transforms the sector’s relationship with external investors, releasing capital for further innovation and growth.

‘Bolstered by the presence of world-leading resources to support technical and market innovation, London undergoes a creative fashion renaissance that cements its position as the world’s creative fashion capital.’

Economic

Consumers increasingly expect ‘omnichannel’ retailing to provide not only a seamless experience between online and physical retail environments, but a relationship to the brand. London’s young designers grasp this; and start to adjust their product and pricing to meet this demand, managing small and frequently turned around collections of stock both online and through outlet and pop-up stores to tap into a younger audience that is curious about new fashion, but sensitive to price.

The success of this approach is most evident in Hackney Walk, where the mix of retail opportunities, studio space and ‘making’ facilities leads to increasing clustering of fashion, marketing, tech and online retail firms, as ‘Tech City’ expands beyond its traditional Shoreditch base to join up with the resulting cluster, a new fashion district stretching from Dalston to Morning Lane.

The resulting cross-fertilisation of design, marketing and software skills fuels the creation of a new generation of responsive online retail platforms and apps offering new fashion and new experiences – at price points to engage trend-conscious young buyers disaffected with a decade of mass-produced ‘athleisure’.

Other private investors, encouraged by the evidence of demand for new types of retail experience and the relative affordability of a large ‘distressed’ inventory of speculatively developed property (for which Brexit has suppressed other demand) set up a constellation of outlets and pop-ups across an arc of East and North East London.

This provides increased access to market for both established designers and new entrants, whose skills in fast fashion and market segmentation have been honed by their experience of designing for online retail.

Attracted by the increased volume of work created by the faster turnaround of new online collections and the demand of the new outlets (and the pop-up stores that spring up within and around them) for constant innovation in both product and retail experience, and aware that their nimbleness gives them an advantage over bigger advertising and marketing firms, small creative/tech agencies increasingly seek to secure their relationships and pair up with new designers.

The resulting hybridisation of content and product development skills leads to exploration of new business models, such as subscription.

Multiplying online, outlet, pop-up and showcasing opportunities become the focus of a new ‘London fashion capital’ campaign – extending the kind of focus that now exists only around the three London Fashion Week showcases to a year-round platform.

Bolstered by a stronger bargaining position with distributors and retailers hungry for ‘Made In London’ product for online, outlet and international markets, and supported by the cluster with the backing of the Mayor’s office, manufacturers successfully lobby ‘mainstream’ multiple retailers for better terms of trade (eg on payment periods and returns.)

To secure their own supply chain, manufacturers begin to underwrite investments in new collections from young London designers that now make up 30-50% of their turnover.

Newly emboldened by international market opportunities and awash with private investment, graduates of London’s fashion schools begin to form a new generation of ‘born global’ businesses, mixing the best of London’s creative, technical and entrepreneurial ‘edge’ with the ‘diaspora’ resource of access to large scale manufacturing opportunities in their ‘home’ countries, but retaining the IP in London.

Social

Accelerating market and technological change has now closed the gap between the atelier, the head office and the factory floor; and demand for labour has increased. The resulting new skills gaps and shortages need urgently to be plugged. Industry, schools and colleges combine to develop campaigns to promote and provide work experience opportunities within a fashion manufacturing sector that now represents a world leading hybrid of craft, content, marketing, performance management and technology skills to encourage take up of traineeships and flexible apprenticeships amongst 16-24 year olds.

This is accompanied by a demand led (‘voucher’) scheme to encourage manufacturers to invest in their own business management, project management, innovation and marketing capacity.

These measures combine to encourage private sector property developers, designers, manufacturers and distributors to invest over the long term in innovation, plant and skills, creating new sub-sectors and service opportunities and an explosion of new jobs available to people living in those boroughs. (straddles political and social)

Technological

Presence of multiple and distinctive R&D facilities – LCF Digital Anthropology Lab, Plexal and other private sector co-working spaces and maker labs drawn by the demand – attracts a wave of new investment in fashion tech propositions, including from foreign- owned labels and manufacturers

Increased collaboration with creative and tech firms has the beneficial side effect of encouraging designers to adopt software and productivity tools that allow them to strengthen their garment tech skills. This in turn helps them to work more effectively with manufacturers, more of whom start to promote their services to new labels as a result. New online platforms and apps proliferate, offering fashion audiences opportunities to cocreate anything from personalised garments to whole ranges.

Improved cashflow and greater confidence in the security of demand from a range of online and physical distribution platforms stimulates manufacturers to invest both in new technology and in new agile management and production skills to enable them to diversify and respond to the faster turnaround of new product demanded by this changed environment.

The focus on developing the adoption of emerging and enabling technologies within the creation, promotion and consumption of fashion aligns with Innovate UK strategy, allowing the sector to attract unheralded levels of public investment in innovation. On the basis that fashion is something that we all engage with every day, the interdisciplinary applications of those discoveries in a range of adjacent fields of health, sport, home and smart cities technology, promoted as ‘lifetech’ through Plexal, transforms the perception of fashion among private sector tech investors. Fashion is now seen by industry and policy makers alike as one of the main channels through which the discoveries of science and technology research can be translated into successful commercial applications. London’s success in identifying itself as the world’s leading centre for this activity engages a ‘virtuous cycle’ of investment in research, development and commercialisation.